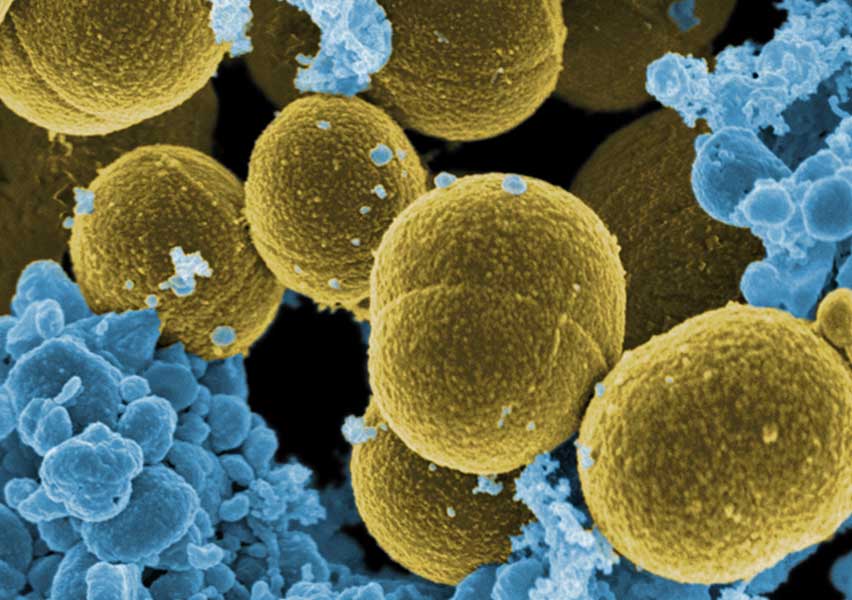

Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a widely distributed pathogen in the human population, with nasal colonization found in approximately 30% of healthy adults and skin colonization in about 20%. These figures increase significantly among hospitalized individuals or healthcare workers. It is one of the leading causes of nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections worldwide, facilitated by its presence on skin and mucosal surfaces and its ability to enter the bloodstream via surgical wounds, catheters, or other invasive medical devices.

Clinical features: S. aureus can cause a broad spectrum of diseases, ranging from relatively benign superficial skin infections (folliculitis, furuncles, impetigo) to life-threatening conditions such as cellulitis, deep abscesses, osteomyelitis, pneumonia, meningitis, sepsis, and endocarditis. It can also cause gastrointestinal illness due to the ingestion of food contaminated with its heat-stable enterotoxins. Certain strains produce specific toxins responsible for clinical syndromes like toxic shock syndrome (TSST-1) and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS). Immunocompromised individuals, hospitalized patients, or those with implanted medical devices (such as vascular catheters, artificial heart valves, or joint prostheses) are at increased risk for systemic infection. Transmission typically occurs via direct contact with infected or colonized individuals, although it can also be spread through fomites or, less commonly, via respiratory droplets.

Cutaneous infections often present with redness, swelling, pain, and abscess formation. In more severe cases, the bacteria may spread through the bloodstream, causing bacteremia and secondary infections in distant organs. Respiratory infections such as staphylococcal pneumonia often follow influenza, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals or those undergoing mechanical ventilation.

Diagnosis: Diagnosis of Staphylococcus aureus infection is based on the isolation and identification of the bacterium from clinical samples (pus, blood, sputum, etc.) using culture techniques, Gram staining (Gram-positive cocci in clusters), and biochemical tests such as coagulase (positive), catalase (positive), and mannitol fermentation. In hospital settings, rapid tests are used to detect methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA), including PCR detection of the mecA gene or latex agglutination tests. In systemic infections, blood cultures and imaging studies may be required to identify deep-seated infection sites.

Treatment: Treatment depends on the susceptibility profile of the bacterial strain. Penicillinase-resistant penicillins (such as oxacillin or nafcillin) or first-generation cephalosporins are effective against methicillin-sensitive strains. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) requires antibiotics such as vancomycin, linezolid, or daptomycin. In mild or community-acquired cases, clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline may be used, guided by susceptibility testing. For deep infections or those associated with medical devices, antimicrobial therapy should be combined with removal of the infected device (e.g., catheters, prostheses, surgical drains). The growing antibiotic resistance of S. aureus poses a major clinical challenge, highlighting the importance of rational antibiotic use and strict infection control practices, such as hand hygiene and hospital surveillance.