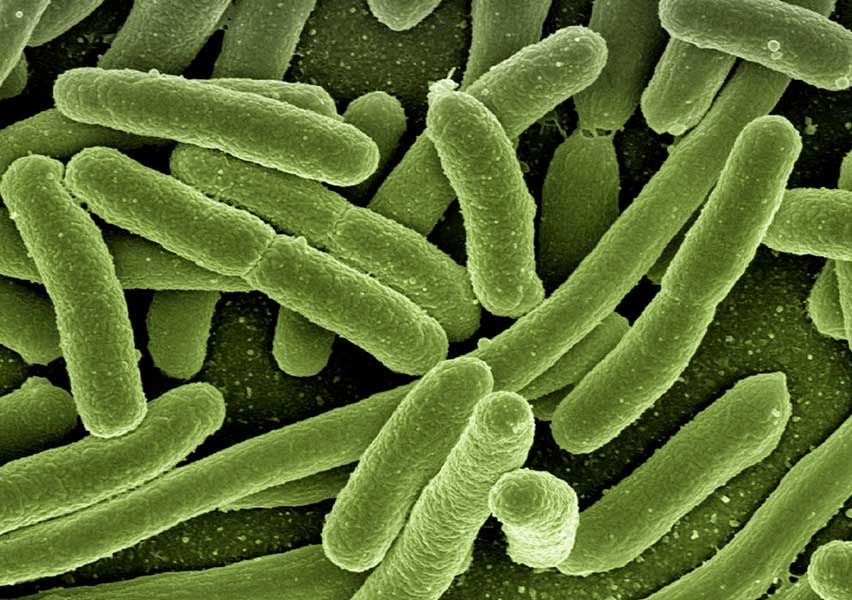

Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli is a facultative anaerobic Gram-negative bacillus commonly found as a commensal in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals. Although most E. coli strains are harmless, certain pathogenic variants have acquired specific virulence factors that enable them to cause both intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most frequent clinical presentation, accounting for the majority of E. coli-related illnesses, followed by gastrointestinal infections and, more rarely, invasive disease such as sepsis and neonatal meningitis.

Clinical features:

Escherichia coli can be divided into several pathogenic groups based on virulence mechanisms and site of infection. The most common clinical presentation is ascending urinary tract infection, especially in women, and includes cystitis, pyelonephritis, and occasionally prostatitis or pelvic inflammatory disease. In neonates, E. coli is a leading cause of bacteremia and meningitis, particularly the K1 serotype, which possesses a polysaccharide capsule that allows evasion of phagocytosis and complement-mediated killing, facilitating central nervous system invasion.

Several enteric E. coli pathotypes are responsible for diarrheal diseases:

- Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC): This pathotype is a common cause of traveler’s diarrhea and infantile diarrhea in low-income countries. It produces heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) enterotoxins that disrupt intestinal electrolyte homeostasis by stimulating adenylate or guanylate cyclase activity, leading to watery diarrhea and occasional vomiting, typically without mucosal inflammation or cell invasion.

- Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC): These strains invade and destroy the colonic epithelium similarly to Shigella spp., leading to an inflammatory diarrhea which may be watery or bloody, often accompanied by fever. They harbor the ial gene and can spread intracellularly between epithelial cells.

- Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC): A major cause of infantile diarrhea in developing countries, EPEC adheres to intestinal epithelial cells using a type III secretion system encoded in the bfpA locus, causing effacement of microvilli and cytoskeletal rearrangement via actin polymerization. This results in prolonged, watery diarrhea, sometimes accompanied by fever and mild inflammation.

- Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC): EAEC adheres to intestinal cells in a characteristic “stacked brick” pattern without invasion or overt morphological damage. However, it produces ST-like toxins and causes persistent, often chronic diarrhea, particularly in malnourished children, immunocompromised individuals (e.g., HIV/AIDS), and residents of tropical regions.

Extraintestinal infections by E. coli may occur when intestinal barriers are compromised (e.g., in ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease, trauma), allowing translocation of bacteria to the bloodstream or adjacent structures. This may result in peritonitis, hepatobiliary infections, skin and soft tissue infections, or pneumonia. Bacteremia can also occur without an identifiable entry point.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of E. coli infections is based on culture or molecular testing of appropriate clinical samples (e.g., urine, blood, stool). In cases of suspected enterohemorrhagic strains (e.g., O157:H7), special culture media and notification to the laboratory are required. Molecular assays may identify virulence genes associated with specific pathotypes (e.g., lt, st, ial, bfpA).

Treatment:

Empiric antibiotic therapy is initiated based on the site and severity of infection and tailored according to susceptibility results. Resistance is common to ampicillin and tetracyclines, and increasingly to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) and fluoroquinolones. Therapeutic options include β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, carbapenems, nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin, and more recently developed agents such as cefiderocol and eravacycline.

Infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli pose significant treatment challenges and often require carbapenems or novel β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Fosfomycin remains a valuable oral agent for lower urinary tract infections caused by multidrug-resistant strains.

Importantly, antibiotic treatment is contraindicated in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) infections due to the risk of exacerbating Shiga toxin release, which may lead to hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).